Love for the Hardy Boys

Last night was the San Francisco Public Library’s 14th Annual Laureates Dinner, an event which never fails to remind me how important libraries are in our lives. The evening was great fun, with an eclectic group of authors (Greil Marcus, Frank Portman, Susie Bright, and 25 others), fabulous food (yes, in a library!), and guests dressed up according to the theme, “urban legends.” I attended as a laureate, and spoke to my “salon”–a collection of five tables in a wing of the library–on urban legends and the early role of books in my life. Here are my comments:

Thank you so much for having me. IÂm very lucky to be considered an honorary San Franciscan, to be a part-time resident of a city that values authors and books so much.

I have had an extremely bookish few days in the city. While I live most of the time in New York with my husband, Drew, I had the task this week of cleaning out my childhood bedroom, as my parents moved two months ago to a new house after twenty-five years. My room had become a time capsule, albeit one that was added to each time I visited. I have always been a collectorÂthis week I sorted through piles of photographs and journals and schoolwork; I culled through Herb Caen clippings and Armistead Maupin novels and yellowed tearsheets from the Chronicle magazine.

I saw many of my literary and artistic influencesÂthere was Salinger and Raymond Carver and Fitzgerald; Jay McInerney and Bret Easton Ellis; Pam Houston and Natalie Goldberg. Andy Warhol and David Hockney. The Grateful Dead and the Rolling Stones, and lots and lots of really embarrassing 1990s music on audio cassettes.

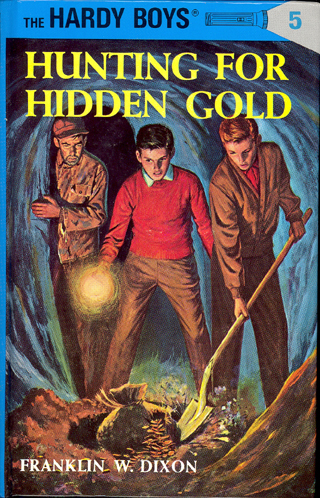

There was one collection I thought coincided rather nicely with tonightÂs theme. It had been packed up years ago and put into a storage unit, but I remembered it, and I wanted to take it with me to the new house. It was my collection of Hardy Boys books. Though they were fictional characters, the Hardy Boys were as real to me as any urban legend, and at eight years old, I thought about them almost constantly.

I would wake up early in the morning and sneak a few chapters; I would take the latest mystery to Town School, where I would read under my desk after I finished my assignments. Luckily, back then, reading was reading, and no one made the distinction between good literature and bad.

The Hardy Boys were my urban legendÂthough the books had been written as early as 1927, even in the 1980s, they seemed incredibly current. I started digging deeper into their world; I even wrote to the publisher, Grosset and Dunlap, asking for more information on the series, though I never got a reply.

I spent many afternoons with my friend, Jason Bley, who is here tonight, searching for rare editions of the series. We would take the bus to Green Apple Books on Clement Street, where we would sit in the stacks for hours, debating the merits of each copy for sale. Used copies went for fifty cents or a dollarÂtwo dollars was expensive, and ten dollars was a verifiable investment. Was a pristine fourteenth edition of The House on the Cliff better than a third edition with a tattered cover? Did it really matter that my copy of The Mystery of the Flying Express was stained with rings of chocolate milk? Green Apple Books wasnÂt a library, but we attempted to turn it into one, reading entire portions of novels while sitting on the floor of the dusty shop.

The books were quirky, and they were specifically designed to appeal to adolescent boys. Every chapter ended with a cliffhanger. There were detailed descriptions not only of car and boat chases, but also of elaborate meals and home life. The books never used the verb Âto sayÂÂcharacters would interject, suggest, deny, or exclaim, creating a roller coaster ride of a narrative in which every sentence was breathlessly uttered. The stories were about crime, but they werenÂt really about evilÂthey were more about friendship and the bond between two brothers. According to writer Arthur Prager, “Never were so many assorted felonies committed in a simple American small town. Murder, drug peddling, race horse kidnapping, diamond smuggling, medical malpractice, big-time auto theft, even (in the 1940s) the hijacking of strategic materials and espionage, all were conducted with Bayport [their hometown] as a nucleus.”

I found the world of the Hardy Boys and their fellow adventurers in other series undeniably exciting. In fact, had I not gone into fiction writing, I think I might have joined the FBI.

A few months ago, I picked up a copy of The Mystery of Cabin Island (Hardy Boys number eight) at a junk shop, and I read it in an afternoon. While entertaining, it was terribly hackneyed, dated writing. Though I had not read a Hardy Boys novel in twenty-five years, this had always been my suspicion. The boys were a jumping off point, not a final destination.

When I wrote my two recent books for teens, Secret Society and its sequel, The Trust, I would sometimes think about the legend of the Hardy Boys. In a world of texting and Facebook and Gossip Girl, the books represented for me a preservation of American childhood through readingÂboth my own childhood, and the childhood of the books characters, nearly fifty years earlier. I hoped that with my own foray into writing for young adults, I might be able to capture some of what had fascinated me so many years ago.

IÂm saving those boxes of books. My hope is that when Drew and I have children and they are old enough to read, they will sit with them in a window seat somewhere, enraptured, just exactly as I was. Thank you.